In the beginning all creatures were green and vital.

They flourished amidst flowers.

—Hildegard of Bingen

Veriditas

The world has gone green and blooming. “The Green Man” has returned. He lives in the time beyond time, dies and is reborn in the cycle that returns green to us after a long hard winter. I was getting worried, what with the drought turning California yellow and brown and the Polar Vortex in the Mid-west and East leaving snow on the ground into April.

I used to wonder why old people take up gardening. Now I understand. As one’s body goes dry and brittle one lusts for “The Green Man”—the young sap rising, the bud and blossom that promise that life will go on even if we ourselves must face our mortality.

At our house, it’s Dan who tends the roses. I am giddy with the bounty he keeps bringing in from the garden—gorgeous red, yellow, pink, and white blooms bring joy to tables and bureaus, celebrate gods and goddesses, express the wisdom of Hildegard, who married two words—“green” and “truth” to coin the word “veriditas,” describing the moment God heals you with a plant.

|

| Lakshmi with Roses |

My 93 year old mother in Indiana, who is confused about who she is and where, understands the miracle of “veriditas.” She tracks the weather, tracks the state of the trees, tells me in our weekly phone calls about the snow, the wind, the cold that kept her trapped indoors for weeks. She describes the winter trees, how bare they are—no leaves, no blossoms. And yet she muses, they are beautiful, doing their naked dance in the wind. Last Sunday she told me she could see green leaves emerging. There was joy in her voice.

Wild Grass and Cherry Blossoms

Twenty-five years ago when I was working on my first book, The Motherline, I stumbled across the work of Robert Lifton, a psychiatrist who argued for a new psychological paradigm of “biohistorical continuity.” His ideas were informed by his study of survivors of the atomic blast in Hiroshima. I quoted from his book, The Broken Connection:

Immediately after the bomb fell the most terrifying rumor among the many that swept the city was that trees, grass, and flowers would never again grow in Hiroshima. The image contained in that rumor was of nature drying up altogether, life being extinguished at its source, an ultimate form of desolation that not only encompassed human death but went beyond it. The persistent and continuing growth of wild “railroad grass”…was perceived as a source of strength. And the subsequent appearance of early spring buds, especially those of the March cherry blossoms, symbolized the detoxification of the city and (in the words of the then mayor) “a new feeling of relief and hope.”I wrote: “It is fitting that those who survived the atomic bomb would be the ones to remind us of the simple and profound truth that we are children of the earth, participants in seasonal cycles, dependent upon the continuity of plant and animal life for our own lives.“ We are approaching Earth Day three generations since the bombing of Hiroshima. Our fears have shifted from nuclear war to catastrophic climate change. As a culture we’ve come no closer to honoring the essential truth which Lifton named. Psychologists have been busy inventing new terms to express the wounds we suffer as a result of our dislocation from the natural world. Here are a couple:

Solastalgia is a term coined by Glenn Albrecht, an Austrialian environmental philosopher. A mash-up of “solace, “desolation, and “nostalgia,” it describes the inability to derive comfort from one’s home due to negative environmental change.

Nature Deficit Disorder refers to a hypothesis by Richard Louv that human beings, especially children, are spending less time out of doors, resulting in a wide range of behavioral problems.If you recognize these disorders in yourself or those you love, please save the date, Nov. 5th 2014. My fellow writers Leah Shelleda, Patricia Damery, Frances Hatfield and I will be doing a writing workshop, Wounded Earth, Wounded Psyche, at the Jung Institute in San Francisco. We will address the need to find language to express our experiences of climate change, our grief, fear and hope for our mother earth.

|

| The Green Man |

The Green One

There is a danger that we can become so paralyzed by our “Solastalgia,” so trapped in our “Nature Deficit Disorder” that we don’t take in the beauty of the trees leafing, the roses blooming, don’t experience the earth as fragrant and alive, don’t hear birds singing or bees buzzing, don’t feel the joy the survivors of Hiroshima felt at the sight of wild grass and cherry blossoms, or the joy I heard in my mother’s voice describing the greening trees. We need the truth of green and the green of truth that Hildegard called “veriditas.” We need that vegetative god the pagans call “The Green Man” or “Jack’o Green.” We need “The Green One” of Islamic Sufism, who is a ‘mediating principle between the imaginary and physical world and a voice of inspiration to artists.’ We need to be healed by plants.

“The Green One” needs our worship, our love, our joy, He leaps into poems, demanding my attention, taking me out of historical time and into the “time before time” or picking me up on his camel, and bringing back my toddler self to feel the joy of spring. Here he is in a section of my poem, “A Creation Story,” about Mesululu who created the world, made mountains, made valleys, made oceans, made children, made bear eagle coyote whale, but was still lonely:

What was it she needed?

What would made her glad?

She played with her hair

She played with her own sweet spot

Til she shimmered and flowed and lo!

A Green Man appeared. He had leaves

For hair and leaves for clothes

And shimmer and glow for his eyes

His name was Abradabra…

It was he

Who tossed his shoe

Into that big old empty

Who stirred life into Mesululu

Sang her song to the stars

Made her laugh

Which flowed her hair

Into rivers and hills

Which shimmered her breath

Into flickering fire and the children

Sit round it and laugh, remembering

How their parents would argue about

Who came first, who made whom

You who’ve forgotten the fire

You who’ve forgotten the hair of your Mother

Her shimmer her flow

And the glow in the Green Man’s eyes

You who belong to your cars

To your hand held devices, your face book wall

I wish you the Green Man’s spell

I wish you the web of the Mother

May he fill your dreams with whales and coyotes

May she braid herself into your breath

May you sit round a flickering fire

And remember how lonely you are

For shimmer and flow

For forest and river

For bobcat and salmon and snake

For Abradabra and Mesululu

For the magical time before time

When you came from below the beyond

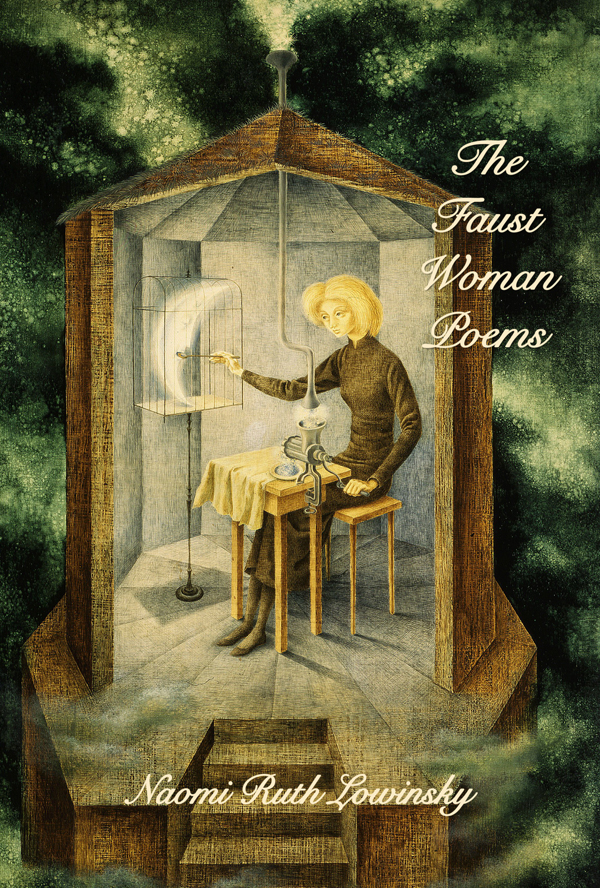

(published in The Faust Woman Poems)

The Sufi Green One leapt into my poem when I was reading Rumi. He is associated with Khidr, which means “The Green One,” an inner figure in Islamic mysticism, a kind of spirit guide. The poem took me places I did not expect to go, which is, I guess, the nature of “The Green One.” I was further surprised and pleased that “The Green One” found its way into a literary magazine, Minetta Review. May “The Green One” take up residence with you.

The Green One

has taken up residence

in my garden bursts out

of the pruned roses tosses laughter

into the fountain flings hummingbirds

into the shimmering He disdains

the clock insists it’s time

for me to learn his dervish whirl

in the meadow after rain He has no patience

for my aching joints forgetting that I’m no

excited toddler reaching for the bright

beyond the trees He refuses to distinguish

between this life

and the ones I have imagined

the ones I’ve dreamt

in which I wander ancient lands

hand in hand with The Green One

who lets the sun into my winter cave

who whirls me out of time’s confines

who makes the sap rise

who makes the lilies of the valley speak

in their forgotten tongues He’s crow

on a branch above my head He laughs

because I don’t know how

to ride the rapture currents

to the thunder world He leaves me dazed

confused and soaking wet then rides by on a camel

scoops me up carries me off to his tent his hookah visions

of a garden with a fountain laughing

among roses a humming bird that hovers

in the shimmering and I am

an excited toddler

reaching for the bright beyond

the trees

For forest and river

For bobcat and salmon and snake

For Abradabra and Mesululu

For the magical time before time

When you came from below the beyond

(published in The Faust Woman Poems)

The Sufi Green One leapt into my poem when I was reading Rumi. He is associated with Khidr, which means “The Green One,” an inner figure in Islamic mysticism, a kind of spirit guide. The poem took me places I did not expect to go, which is, I guess, the nature of “The Green One.” I was further surprised and pleased that “The Green One” found its way into a literary magazine, Minetta Review. May “The Green One” take up residence with you.

The Green One

has taken up residence

in my garden bursts out

of the pruned roses tosses laughter

into the fountain flings hummingbirds

into the shimmering He disdains

the clock insists it’s time

for me to learn his dervish whirl

in the meadow after rain He has no patience

for my aching joints forgetting that I’m no

excited toddler reaching for the bright

beyond the trees He refuses to distinguish

between this life

and the ones I have imagined

the ones I’ve dreamt

in which I wander ancient lands

hand in hand with The Green One

who lets the sun into my winter cave

who whirls me out of time’s confines

who makes the sap rise

who makes the lilies of the valley speak

in their forgotten tongues He’s crow

on a branch above my head He laughs

because I don’t know how

to ride the rapture currents

to the thunder world He leaves me dazed

confused and soaking wet then rides by on a camel

scoops me up carries me off to his tent his hookah visions

of a garden with a fountain laughing

among roses a humming bird that hovers

in the shimmering and I am

an excited toddler

reaching for the bright beyond

the trees

|

| Khidr |