Oh freedom, oh freedom, oh freedom over me

And before I'd be a slave I'll be buried in my grave

And go home to my Lord and be free

—“Oh Freedom”

Mississippi Freedom Summer 1964

The freedom train is coming, can't you hear the whistle blowing

Its time get your ticket and get on board

Its time for all the people to take this freedom ride

Get it together and work for freedom side by side

—“Freedom Train”

Recently Dan and I watched Public Television’s searing documentary, “Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964.” We were both flooded with memories of a powerful time in our lives, years before we met each other, when we were twenty-somethings, on opposite coasts, both married young with babies. We each remember our shock and horror at the vicious murders of the three civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman. When I saw Andrew Goodman’s face in the documentary I gasped. He looked so much like Dan did in photos I’ve seen of him in his twenties—a smart, idealistic, dark haired Jewish boy from New York. He even went to Queens College, as did Dan.

Dan tells me that Freedom Summer was “the thing I missed.” He had wanted very much to go to Mississippi that summer, wanted to make a difference, to take initiative in registering voters despite what was a brutal and difficult environment. He knew about the atrocities and the disappearances, about Medgar Evers’ assassination, about the lynching of Emmet Till. He knew the meaning of the song “Strange Fruit.” He was already a civil rights activist; he had helped organize boycotts and picketing of Woolworth Stores in support of the first sit-ins, had participated in the 1963 March on Washington, had opened his home to strangers who came from afar to March for Jobs and Freedom. The March reinforced his feeling that he was part of something bigger than himself. He was working with the American Friends Service Committee on a project to end discrimination in housing in the Washington, DC suburbs, He saw Freedom Summer as an important next step in the Civil Rights movement. He supported the strategy of sending young black and white civil rights workers south to register African Americans to vote. He knew it would be dangerous and with a young wife and a new baby daughter he decided not to go.

Free Speech Movement, Berkeley 1964

I'm walking and talking with my mind

stayed on freedom

Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah.

Ain't nothing wrong with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Many young Americans were initiated in the fire of that summer. Mario Savio, whose courage would touch my life, was one of them. He came to Berkeley after volunteering in Mississippi to raise money for SNCC, only to learn that the University was banning political speech and fundraising. I was an undergraduate at Berkeley at the time, with a husband commuting to medical school in San Francisco and a baby boy at home. I participated in the Free Speech Movement and was moved by Mario Savio’s passionate speech:

There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can't take part; you can't even passively take part, and you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you've got to make it stop. And you've got to indicate to the people who run it, to the people who own it, that unless you're free, the machine will be prevented from working at all!

But I did not join my fellow students to sit-in at Sproul Hall. I wasn’t really cut out to be an activist, though I didn’t know that at the time. I did know I was a writer and that I wanted to be part of my generation’s big experiences. Like Dan, I felt the powerful surge of historical change, but having taken on adult responsibilities young, I had to think of my child—I couldn’t risk jail.

Free to Be You and Me

Come with me, take my hand, and we'll run

To a land where the river runs free…

To a land where the children are free…

And you and me are free to be you and me

We were in love with freedom in those years, sexual freedom, women’s freedom, African American freedom, students’ freedom to gather and protest. We were determined to express ourselves, become ourselves, love across ethnic and racial boundaries, expand our consciousness, follow our stars. Freedom is, after all, America’s muse—muse to the French and American Revolutions, muse to Thomas Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence, muse to Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad, muse to Dan’s father, a music loving seventeen year old who stole himself out of the anti-Semitic Polish army, muse to my family who stole themselves out of Hitler’s Europe to the “land of the free.” We on the left claimed freedom as our muse in the 60s. It’s interesting nowadays, to see freedom as the darling of the right who seem focused on the freedom to bear arms and the freedom of the wealthy to spend a fortune to support their politics.

The long view from maturity reminds us that freedom can be fickle and dangerous. As a student writing for the Queens College student newspaper, Dan recalls mocking a speech by the president of the College who said, “There is no freedom without restraint.” Yet, just a few years later he understood the need for restraint by not going to Mississippi for Freedom Summer, despite wanting very much to do so. In the long view it’s clear that he made the right decision. It was part of his nature, part of becoming himself. Dan has always been a family man, devoted to his children, as well as an activist, mixing a pragmatic and realistic streak with his idealism. Just a few years later he was able to go to Mississippi to make a difference as a trainer for the Child Development Group of Mississippi, a statewide Head Start Program. He learned how freeing and empowering it could be for poor African American parents to get engaged in their children’s schools. This inspired him to become an activist for parent involvement in his own children’s schools.

The long view has taught us that the freedom to become oneself is a meander, dependent on luck, fate and plodding perseverance. It is the inner capacity to follow one’s truth and passion free of the tyranny of collective attitudes but with respect for the truth and passions of others. I feel blessed to have lucked into a line of work—Jungian Analysis— that supports people in the process of freeing themselves to live full creative lives. The etymology of the word ‘free’ is telling. Roots in Old German and French associate freedom with love, friendship and safety. Dan and I are lucky to have found the freedom to be ourselves with each other.

The long view has given me the freedom to see the consequences of my youthful passions, to see their shadow side. I expressed this in a recent poem “Demeter Beside Herself.” It is one of three new poems just published in the online journal Stickman Review. The poem is in the voice of the goddess, whose daughter “is off becoming /someone I’ve never been.” This daughter “wants power,” wants digital devices,” “wants electricity all night long.” All this has thrown her mother “out of orbit.” I am that mother. I am that daughter.

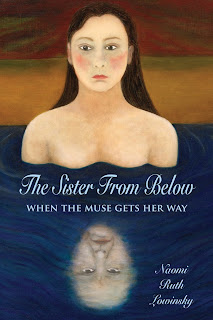

Retirement has freed Dan to do his good works in our community for free. Working less has freed me to write and publish more. I’ve been lucky in my long meander as a writer, to have wandered into the world of Psychological Perspectives, a wonderful journal published by the Los Angeles Jung Institute, which has so long supported my freedom to follow the weird wild places my Muse takes me, by publishing so many of my poetic essays. They’ve just done it again. The latest issue of Psychological Perspectives includes my essay “Abracadabra Tongue: On Poetry Magic” in which my poems and active imagination with dream figures lead me to fly on a magic carpet with the Muslim Solomon, and to an encounter with the Queen of Sheba, the beautiful dark Queen of Ethiopia, who reveals the lusty “old black magic” version of her rendezvous with King Solomon. I hope you’ll read all about it.