|

| “Lady Liberty” by Theodore Bonev St. Martin |

We Dissent: There are few greater incursions on a body than forcing a woman to complete a pregnancy and give birth. For every woman, these experiences involve all manner of physical changes, medical treatments (including the possibility of a cesarian section), and medical risk. Just as one example, an American woman is 14 times more likely to die by carrying a pregnancy to term than by having an abortion…

Today’s decision strips women of agency…It forces her to carry out the State’s will, whatever the circumstances and whatever harm it will wreak on her and her family. In the Fourteenth amendments terms, it takes away her liberty.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women Health Organization Dissent, by Stephen Breyer, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomajor.

|

| Musing in the Desert by Jeremy Bishop |

An Awful Bleakness of Being

The Muse of Free Women has gone on retreat. No one knows where or why. You say: “It’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—the overturning of Roe v. Wade—that upsets Her.” True. But She left us much earlier, went off, it is said, to the desert, alone. Women have stopped celebrating Her, praying to Her, bringing Her offerings. Maybe She’s learning how to ride a camel over the Abyss. Maybe She’s praying for Our Mother the Earth, whose future looks bleak. Maybe She’s waiting for America’s psychotic episode to be over. Could the recent good news, about the Inflation Reduction Bill which addresses Climate Change, or the surprising vote for Women’s Freedom in Kansas, which rejected an attempt to overturn the existing constitutional right to abortion in Kansas, lure Her back to us?

Like most women in America, I felt gut punched by the Supreme Court’s Ruling in Dobbs, ending a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion. We knew it was coming but it continues to feel unreal that so many women will have to return to back-alley abortions or, for those who can afford it, trips to faraway places. Maureen Dowd, in her NYTimes Opinion Column, quoted the author Niall O’Dowd: “Now that the world has turned upside down, there will be charter flights from America to Ireland for abortions.” Remember, Ireland was virulently anti-abortion until 2018, when the Irish voted to legalize it, and to free women. Dowd wrote:

Ireland and the United States have traded places. Ireland leapt into modernity, rejecting religious reactionaries’ insistence on controlling women’s bodies. America lurched backward, ruled by religious reactionaries’ insistence on controlling women’s bodies.

Once, Ireland seemed obsessed with punishing women. Now it’s America. (July 17th, 2022)

|

| An Awful Bleakness: “Magdalena” by El Greco |

An awful bleakness of being descended upon me in the wake of the Supreme Court decision. I have heard that word—bleak—from so many women, on media and in my life. Did you feel it? It’s as though our inner world has turned into a barren, dangerous landscape where women are shamed and punished just for being women—made to cover our hair and faces, not allowed to be part of the world of school, sports, work, politics, the arts. Have we been transported to Afghanistan, where, just a year ago, women’s rights and freedoms were torn away from them as the Americans left and the Taliban took over? Have the Taliban taken over America?

|

| The Patriarch: “Zeus” by Jacob Potma |

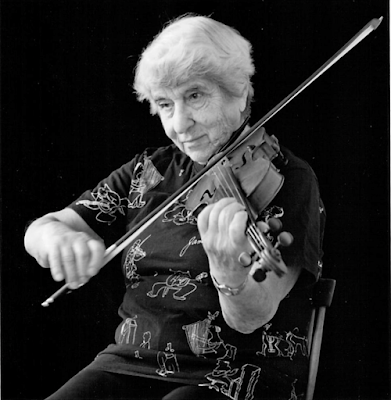

In Thrall to the Patriarchy

I grew up in a Patriarchy. Always attuned to my mother’s feelings—though she never spoke of them to me—I felt her inner bleakness as she trudged around like a pack animal doing my father’s bidding—typing his manuscripts, tending to us children, doing all the housework and cooking, having no life of her own. Years later, after she left my father, my mother became one of the freest, most self-actualized women I knew in her generation. She made a rich life for herself, doing what she loved—working with young children, playing violin and viola in chamber groups and orchestras, giving music lessons. She traveled to Prague because there was a workshop on performing Bartók she wanted to take. She travelled to Florence, to visit me and Dan when we were there for a conference, and then went off to visit friends in Northern Europe, laughing at us when we worried about her plan to spend the night in the train station, which she did, and was just fine.

|

| Mother Doing Her Thing |

Mother died in 2018. I’m grateful that she did not live to see her granddaughters and great granddaughters lose their rights. The Patriarchy has spoken. It has cut women’s freedom out of the American constitution, handed it over to the states. It has enacted its misogynous cruelty over women’s bodies and souls as it has for thousands of years—stigmatizing and controlling women and girls as though our only function is to be vessels for new life. Our bodily autonomy, our right to make our own decisions about childbearing has been plundered in many states in American—the so called “land of the free.” Our freedom to travel to nearby states that allow abortion is in question. If a basic right we’ve had for close to fifty years can be torn out of the constitution by a virulent minority, if our dignity can be denied, our authority over ourselves ripped up like a contract that has been reneged on, how are we equal citizens? Like Jews forced to wear the Yellow Star, we walk on dangerous ground, unsure what will set the powers that be against us.

The Patriarchy has determined that it owns our wombs. It is up to them and not to us what use we put them to. The Supreme Court has determined that my uterus belongs to the state I live in. I am lucky to live in California, and to be past the age of childbearing. But what of my granddaughters? The Patriarchy has plans to make the abortion ban federal. What if a granddaughter should need an abortion, or have a miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy that requires an abortion-like procedure to save her life? It was up to the state of Ohio to determine whether a ten-year-old girl, raped by a twenty–seven–year old man, could have an abortion in her home state. “Not in Ohio! Not even in cases of rape or incest!” the child and her parents were told. She had to be driven to nearby Indiana, where a gutsy doctor did the procedure. Sadly, that doctor has been harassed and threatened. Sadly, Indiana has changed its mind on abortion. Another child in that situation will need to be driven all the way to Illinois. Would her freedom to travel remain intact? Or would she and her doctor be at risk under the brutal law of the Patriarchy?

Don’t get me wrong, when I say Patriarchy I don’t mean men. The men in my life don’t buy into the hateful ideas promoted by the Supreme Court majority or the people in charge of states like Ohio, Texas and Florida. The men I know consider themselves feminists and value their inner feminine side. In my lifetime I have seen women’s rights and freedoms expanded exponentially. Most Americans, even Republicans, support women’s freedom to choose in childbearing as well as in work and in relationships. What we are seeing, I believe, is an enormous Patriarchal backlash, because some parts of America feel a loss of power and privilege, and because misogyny lives in both men and women’s unconscious. This, accompanied by extreme economic and class inequality, and racism, makes life a living hell for many poor people, especially women with children and women of color, for whom, having to bear an unwanted child can sink them deep into poverty.

|

| “Witches being Burned in Derenburg, 1555” |

Akin to Slavery and to the Inquisition

It is the work of The Muse of Free Women to bring our fierceness and grief out of the woodwork. She comes to me in the form of furious ghosts. The witches of Salem are howling in me. The witches who were burnt at the stake during hundreds of years of the Inquisition, which murdered women of power, women of wisdom, uncanny women who had visions, who knew the medicinal uses of herbs, who were midwives and performed abortions, are moaning and keening in my soul. Women who died too young having back-alley abortions before Roe became law, are weeping in my heart. They cry out:

We thought this was over, that this hatred of us, of our bodies, which are so powerful that no one can be born without coming through us, had ended. That a woman’s power to bear life would be honored. That her right to refuse a child was part of that honoring and basic common sense. What child wants a mother who wishes it had never been born? What child needs a mother whose own life and future is sacrificed in bearing one she is not ready to mother, or can’t afford to feed, clothe and love?

This is not a country that recognizes the essential work of mothering, or that healthy, loved, well–educated children are the backbone of our democracy. We don’t give new parents time off to bond with their babies and make the transition into being parents. We don’t support childcare and make it affordable; we don’t pay childcare workers a living wage; we don’t support early education and pay teachers decently. We don’t support single mothers so they don’t have to work multiple jobs and can be with their children. The unborn child that is so precious to the anti-choice people is on its own and so is its mother. I know there are well intentioned people who are setting up centers to support women who are bearing unwanted children. But from what I’ve heard none of these programs goes very far beyond early infancy. And none can deal with the wound to a woman’s sense of self, when her reality and truth are denied and she is compelled to do something as difficult as bearing a child against her will. Being forced to bear a child is like being forced into a marriage—a violation of the most essential human freedom. Both are akin to slavery. Jamelle Bouie puts it well in an opinion piece in the New York Times of July 17th, 2022:

When a state claims the right to limit your travel on account of your body—when it claims one of the most fundamental aspects of your personal liberty in order to take control of your reproductive health—then that state has rendered you little more than another form of property.

|

| “A Slave Interrupts General Lee’s Breakfast” during the Civil War |

The Motherline

I became a mother very young, age 19, a decade before Roe v Wade freed women to live full lives. I was lucky because I was married, had a mother who loved being a mother, and had family support and resources. But I felt the disrespect for mothers acutely—the Patriarchal attitude that demeans and marginalizes women and mothers. Mothers were a joke in popular culture and blamed for most psychological issues in therapy. For me, having children young was a profound education in life. I learned child development from my children. They taught me the basics of psychology. When I decided to become a psychotherapist, I was infuriated that none of my experience as a mother was valued—none of it could be claimed in a resumé, or help me get into grad school.

|

| Cover art by Sara Spaulding-Phillips Cover of Fisher King Press Motherline |

That fury led to my writing my first book, The Motherline. This year is the 30th anniversary of The Motherline’s publication in 1992. Thanks to my publisher, Fisher King Press, it is still available, and I still hear from women who value it for its alternative view of women’s lives. At the time I wrote it I saw women rejecting their mothers and “wandering like motherless daughters in the too bright light of Patriarchal consciousness.” I wrote that it is “our task to integrate our feminine and feminist selves. We must connect the historical self that was freed by feminism to live in the “real” world, with the feminine self that binds us to our mothers and grandmothers” (p. 32) and to the Deep Feminine. Thirty years later, I still consider this essential. For most women I know, valuing being a mother and wanting to make our own choices about childbearing, are totally interconnected. Here are some quotes from the Motherline that seem pertinent to our times:

The Great Mother, in all of her aspects, is especially fearful for women who identify with feminism and the women’s movement. Many of us broke free of the stranglehold that biology has on our destinies. Surpassing our mothers we charged into the world of achievement and mastery. We want to feel we are living conscious lives directed by muscular egos. The Motherline and matriarchal consciousness are at odds with these goals. The heroism of yin, which opens up the boundaries of the female body to take in seed, allowing new life to grow within it and be born out of it, is seen as a frightening swamp of passivity. Female flesh—fat, breasts, hips—become a fearful shadow…

We are left only with feelings of shame and inferiority for the blood, sweat, desire, and fury of our female experience.

Integrating feminism and the feminine requires bringing to consciousness the Motherline as it is expressed in the very texture of how women talk, the looping that ties together life–cycle experiences…the sacred nature of organic experience. This requires honoring the ebb and flow of a woman’s body…

A woman who can integrate her hunger for the world with carnal self–knowledge lives in relation to her body, as well as to her generation. She can attend to her life’s unfolding from the inner whispers of her dreams, to the interpersonal dialogue with kith and kin, to the collective currents that sweep her time. She knows who she is, where she comes from, where she is going, and what her place is among the living and the dead. (p. 36)

|

| Free Women: “The Witches go to Market, 1876” by Alice Boyd |

What Does it Mean to Be Free?

“Free” is a fascinating word. It means the obvious—“not in bondage.” But its root can be traced back to Sanskrit “priyah,” meaning “love,” or “beloved,” German “Friede,” meaning “peace,” and to the Norse Goddess “Freya” alias “Frigg,” whom Robert Graves, in The White Goddess, associates with the Goddess of Love and Death.”

The Goddess is a lovely, slender woman with a hooked nose, deathly pale face, lips as red as rowan–berries, startling blue eyes and long fair hair. She will suddenly transform herself into sow, mare, birch, vixen, she–ass, weasel, serpent owl, she–wolf, tigress, mermaid or loathsome hag… In ghost stories she often figures as “the white lady; and in ancient religions…as the “white goddess”…The test of a true poet’s vision, one might say, is the accuracy of his portrayal of the White Goddess…The reason why her hairs stand on end, the eyes water, the throat is constricted, the skin crawls and a shiver runs down the spine…is that a true poem is necessarily an invocation of the White Goddess, or Muse, the Mother of All Living, the ancient power of fright and lust…whose embrace is death. (p. 21)

|

| “Freya” by John Bauer |

Barbara Walker, in The Woman’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets has a long entry about Freya:

Great Goddess of northern Europe, leader of the “primal matriarchs”…”divine grandmothers…Freya was…the ruling ancestress…who ruled before the arrival of Odin…Myths say Odin learned everything he knew about magic and divine power from Freya.

The pagans said nothing could be lucky without Freya’s presence…

Freya represented sexual love, which is why her alternate name Frigg became a colloquialism for sexual intercourse.

Walker speaks of Freya’s “Kali–like function as Destroying Goddess, which she would assume when men and gods displeased her by forgetting her principles of right living, justice, honor and peace.” (p. 325) Is it any wonder that when the Patriarchal gods took over, they feared this powerful Muse of Free and Beloved women? In many of the myths, though Freya was married, she was strong willed, slept around, belonged to herself, knew more magic than any other god, wasn’t controlled by any male. It’s not hard to understand the hatred and fear that underlie the dying throes of a Patriarchal mentality that denies the mysteries, tries to gun down death, has forgotten how to live in the dark, in connection with the ancestors, in the vagaries of the moon, in harmony with the seasons and in service to the earth.

|

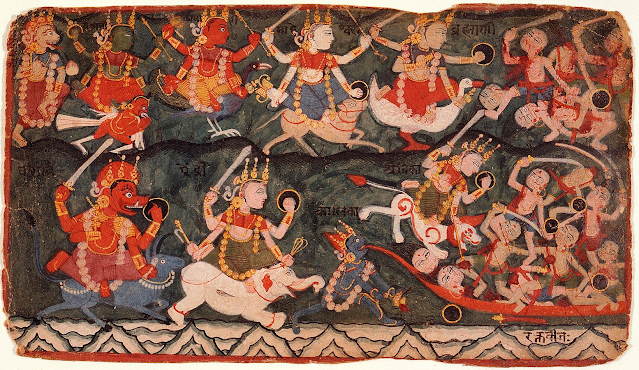

| Goddess Ambika Leads Eight Mother Goddesses in Battle Against the Demon |

Freya the Free, the Beloved, the Terrible

What, you wonder, do we do now? How so we get our Muse, our Beloved, out of the desert to free us? She’s scary. She’s uncanny. She makes no sense to the Patriarchal mind, which punishes us for Her powers. And yet She is in us, of us, and we need Her badly.

She’s been with me since I lived in India, as a young woman with young children. India is full of images of powerful Goddesses fighting demons. The Goddess changed my life by helping me understand the cycles of birth and destruction and the distinction between personal, cultural and archetypal experience.

|

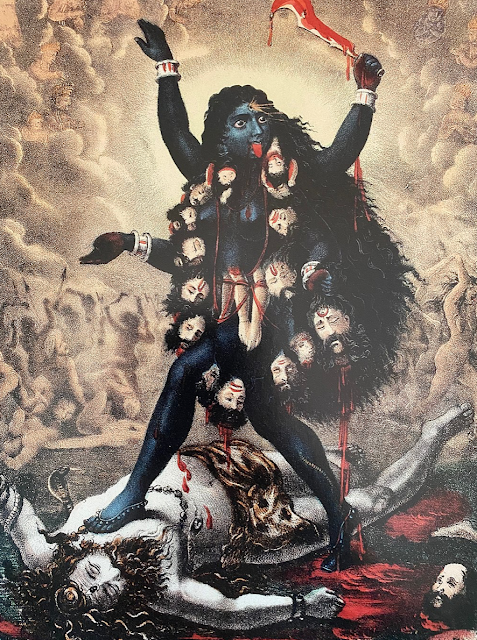

| “Goddess Kali” Calcutta Art Studio, 1883 |

She came to me as Kali, who gives birth and death in one fell swoop. As I was wrestling with writing The Motherline, I came to understand that Kali is essential to female psychology:

Every woman has a Kali side, every mother has a secret devourer, a baby killer in her soul. When contemporary women write honestly out of their lived experience, they wrestle…with their Kali natures; they dare to name…their murderous impulses…(p. 195)

At a psychological level the abortion issue is about our capacity to confront Kali consciously. Those who would deny women the right to choose abortion seek to control Kali by forcing women to bear children. Kali will then take other forms: ruined lives, neglected and abused children, women maimed or killed in illegal, back–alley abortions. However those who support a woman’s right to choose abortion also need to face the truth that…abortion is not merely a medical procedure. It is the tearing from the womb of our own flesh and blood. It is a sacrifice of life, hopefully for life. (pp. 196-97)

To bear her children, her mother, her life in the presence of Kali…requires that a woman know her carnal self, bear her mother’s pain and limitations, face the bones of her ancestors and the bloody truth that she has no control over what she is born into, or what she gives birth to…; though we have our human responsibility, we are not in charge of destiny…Our personal mothers are not to blame for what is in the nature of human life. [Kali] links us to the blood and bones of our female knowledge, to our mother’s suffering as well as our own. She tells us that we are flesh and blood; that we give life and take life, nurture and destroy, suckle and poison; that these are in the very nature of existence, not the fault of women. She knows that it is in the very corruptibility of our flesh that our human souls bloom. She knows that we live in the great hands of history, which can tear our small lives to shreds. (pp. 206)

|

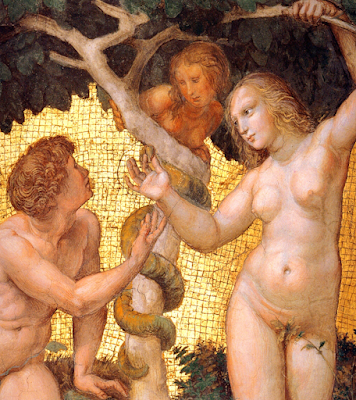

| “Lilith as the Temptress” by Raphael, between 1509 and 1511 |

Whether we call Her Kali or Freya, The White Goddess, the Muse of Free Women, or Lilith, we need to claim Her in our own souls in order to find our footing on female ground. I am reminded of a phrase used by the Jungian Analyst, Irene de Claremont Castillejo, in her 1967 book Knowing Woman, in which she called a woman’s ability to choose whether or not to bear a child “the Second Apple.” The first apple is the one Eve tempted Adam to eat from the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The Second Apple is the one every woman tastes when we make the choice to use contraception or to have an abortion. That is how Eve becomes Lilith—Adam’s uppity first wife who refused to lie beneath him and was sent into exile by the Red Sea—how she loses her innocence, faces her shadow, takes responsibility for her freedom. In Raphael’s version of the story, Lilith and the Serpent/Satan are the same. Tasting the Second Apple is always dangerous and essential. Women are eating Forbidden Fruit all over the country and handing it out to others. How do we support them?

Donate! Did you know there is an abortion clinic in Portland, Oregon called “Lilith”? Those women in Oregon are calling her back from her exile. There are brave women and men all over the country opening abortion clinics in states that allow them. Send them money as your way of offering others the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, which grows on female ground. Whole Woman’s Health, for example, was an abortion provider which, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, went all the way to the Supreme Court, taking on Texas’ Abortion law, which outlaws abortions after a fetal heart beat is detectable (usually 6 weeks) and authorizes the public to become bounty hunters and sue anyone who performs, aids or abets a post–heartbeat abortion. This law sent shock waves of terror into those who support women’s rights. Women usually don’t know they are pregnant by six weeks and certainly can’t arrange an abortion that quickly. Which means you can’t get an abortion in Texas. Whole Women’s Health is moving to New Mexico. Its Abortion Wayfarer Program helps free women to find the medical help they need.

Vote! Your vote in the mid-term elections is essential. Vote for those who support Women’s Rights and Freedoms. Help get other women registered to vote by donating to Register Her.

|

| Suffragettes, 1917 |

Pray! Call Her into your life! Do whatever you do to invoke the Muse or the Goddess. She shows up in unexpected places. She showed up as I was working on a poem about the storming of the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. She stands on top of the dome—beautiful, strong, a woman of color. She is known as Freedom—a manifestation of Lady Liberty. Notice that Freedom wears feathers in her hair, and a beautiful blanket wrapped around her, Indian style. Her story holds some of the shadow truths we like to forget. She was created just before the Civil War, when the Capitol Dome was being rebuilt. Her creation was facilitated by a brilliant slave, Philip Reid, “who came up with the idea of using a pulley to move the statue, was then paid $1.25 a day by the federal government to ‘keep up fires under the moulds,’ according to the architects records.” His owner pocketed the money. But when the final cast of the Statue was raised in 1863, Reid was a free man. It took until 2014 for his contribution to be recognized in a ceremony on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation.

|

| “Freedom,” by Thomas Crawford, 1863 |

The Day They Roughed Up Lady Liberty

|

| Armed with a Lyre, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1842 |

She Sings a Different Story

May Freedom be your Goddess, your choice, your labor. May Freedom be our rebirth into love for our Mother, the Earth, and for all creatures—flora and fauna—including one other.

|

| “Joy of Life: The Quintessential Maternity of Nature” by Mrinal Kanty Das” 2016 |

Special Offer:

A limited number of signed copies of the hardcover first edition of the Motherline, originally called Stories from the Motherline, is available for $20.00 each, which includes shipping. You can request a copy at danielsafran@yahoo.com.

(San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch, 1983), p. 240.

(San Diego: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch, 1983), p. 240. (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985), p. 91.

(London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985), p. 91. (New York: Harper Colophon, 1975), p. xiii.

(New York: Harper Colophon, 1975), p. xiii.