I sink in deep mire, where there is no standing:

I am come into deep waters, where the floods overflow me.

I am weary of my crying: my throat is dried: mine eyes fail while I wait for my God.

Psalm 69

Our Measure of Suffering

Suffering is a powerful muse for poets. Consider the Psalmist, who cries out to God in psalm after psalm, trying to comprehend the meaning of his suffering, and God’s absence. The question of why we must suffer is central to religious thought, to psychology, and to creative work. We turn to the nameless God of the Jews; we turn Christ, to Mary, to Buddha, to Krishna and Ganesha, to the Goddess in all her manifestations, for relief from our suffering. Some of us turn to psychology—we pay attention to our dreams, we try to understand the message in our suffering. Some of us turn to writing, to painting, to dancing, to music.

Jung argues that no life is complete without its “measure of suffering.” He writes, “the opening of the unconscious always means the outbreak of intense spiritual suffering.” This, he explains, is because our rationally ordered world, our known round of days, our walls for safety and our dams to control Nature’s flow, all burst open as Mother Nature seeks revenge for the violence we have perpetrated on her. Jung, who had a strong environmental consciousness, essentially says that suffering, when done in the service of greater conscious, is the way our psyches regain their ecological balance when we have been too one-sided. Suffering is intrinsic to a spiritual path and to a creative path. Our best–laid plans are ripped asunder by storm, by illness, by fate, by death. If you surrender to your suffering, it can become The Way—to a deeper connection to your own nature and to Nature.

But who wants to surrender to suffering? Jung comments: “Because suffering is positively disagreeable, people prefer not to ponder how much fear and sorrow fall” to our lot in life. That’s for sure, especially in our goal oriented and materialistic culture, in which the “pursuit of happiness” is inscribed in our Declaration of Independence. We’re all supposed to “just do it,” and if we do it right our happiness should be revealed to us like the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. If we haven’t found the happiness to which we are entitled it must be because we’re not fighting for it hard enough. Surrender is not our cultural mode.

Heartbreak Hotel

Luckily, there are pockets in our culture that hold a deeper wisdom, Rock and Roll for example. I was suffering the agonies of adolescence when I first heard Elvis, that messenger of sexuality and sorrow sing his anthem:

"Heartbreak Hotel"

Well, since my baby left me,

I found a new place to dwell.

It's down at the end of lonely street

at Heartbreak Hotel.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

And although it's always crowded,

you still can find some room.

Where broken hearted lovers

do cry away their gloom.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

Well, the Bell hop's tears keep flowin',

and the desk clerk's dressed in black.

Well they been so long on lonely street

They ain't ever gonna look back.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

Hey now, if your baby leaves you,

and you got a tale to tell.

Just take a walk down lonely street

to Heartbreak Hotel.

That song expressed my mood quite accurately. The lonely one in me loved knowing that if I took a walk down lonely street I’d find company at the Heartbreak Hotel. The poet in me loved the deep feeling, the images and word play. However I lived in a cultured family in which Elvis was seen as the lowest of low culture. Taboo. If I wanted access to the power of music to express suffering, why not listen to Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion or the Mozart Requiem? I liked Bach and Mozart just fine, but they weren’t sexy, they didn’t dance and grind their hips while they sang about their loneliness. It would be many years before I felt the inner freedom to appreciate Elvis, and follow his lineage back to the Blues where I found so much to love—so much beauty, wisdom and humor in the expression of terrible suffering. Here are some of the lyrics to Howlin Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightnin’” with it’s intense poetic imagery and sound, evoking lost radiance and abandonment.

Whoa oh tell me, baby

With Rock and Roll and the Blues we have moved from abandonment by God to abandonment by a lover. The “whoo hoo” of Howlin’ Wolf’s cry, is the whistle of the train pulling out of the station, is the wisdom that as we suffer life moves on and we never know where we’ll find ourselves next.

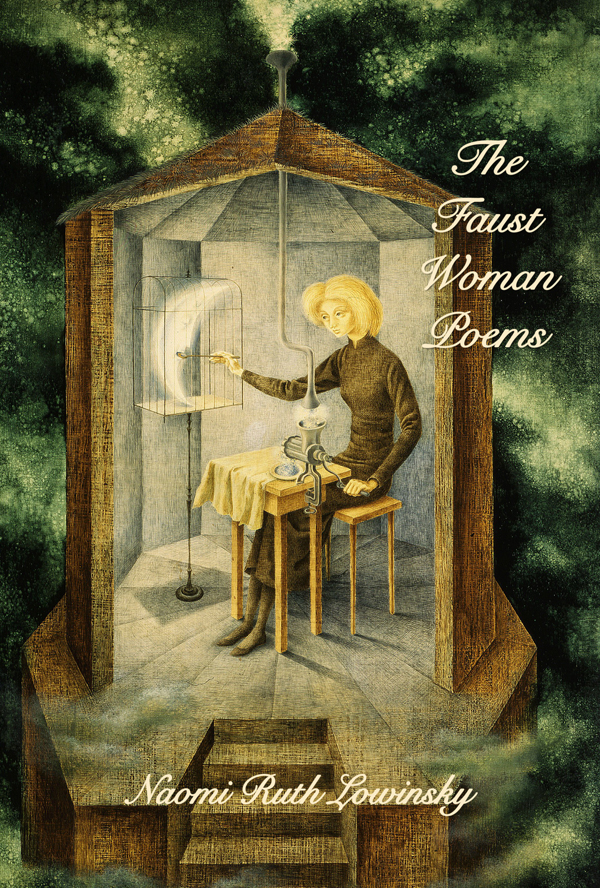

Suffering has always been a major Muse for me. If I can write about it, I have found, I can suffer it and glean meaning from it. I believe I am in good company here, with the Psalmist, Elvis and Howling Wolf and Gilda. And so I close with a poem about suffering, from The Faust Woman Poems.

Because of What Aches

Because your neck tries to rise above

an aging tangle of knots

Because you’ve given yourself to the wild ride—chased after toddlers

broken commandments, had words with the owl on the roof—

Because your eyes long for the mountain

Because the old rose still blooms

You’re not ready for ash, or thin air

Submit to the fire your early drafts

your sagas of shame, your lost directions

Jung argues that no life is complete without its “measure of suffering.” He writes, “the opening of the unconscious always means the outbreak of intense spiritual suffering.” This, he explains, is because our rationally ordered world, our known round of days, our walls for safety and our dams to control Nature’s flow, all burst open as Mother Nature seeks revenge for the violence we have perpetrated on her. Jung, who had a strong environmental consciousness, essentially says that suffering, when done in the service of greater conscious, is the way our psyches regain their ecological balance when we have been too one-sided. Suffering is intrinsic to a spiritual path and to a creative path. Our best–laid plans are ripped asunder by storm, by illness, by fate, by death. If you surrender to your suffering, it can become The Way—to a deeper connection to your own nature and to Nature.

But who wants to surrender to suffering? Jung comments: “Because suffering is positively disagreeable, people prefer not to ponder how much fear and sorrow fall” to our lot in life. That’s for sure, especially in our goal oriented and materialistic culture, in which the “pursuit of happiness” is inscribed in our Declaration of Independence. We’re all supposed to “just do it,” and if we do it right our happiness should be revealed to us like the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. If we haven’t found the happiness to which we are entitled it must be because we’re not fighting for it hard enough. Surrender is not our cultural mode.

Heartbreak Hotel

Luckily, there are pockets in our culture that hold a deeper wisdom, Rock and Roll for example. I was suffering the agonies of adolescence when I first heard Elvis, that messenger of sexuality and sorrow sing his anthem:

"Heartbreak Hotel"

Well, since my baby left me,

I found a new place to dwell.

It's down at the end of lonely street

at Heartbreak Hotel.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

And although it's always crowded,

you still can find some room.

Where broken hearted lovers

do cry away their gloom.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

Well, the Bell hop's tears keep flowin',

and the desk clerk's dressed in black.

Well they been so long on lonely street

They ain't ever gonna look back.

You make me so lonely baby,

I get so lonely,

I get so lonely I could die.

Hey now, if your baby leaves you,

and you got a tale to tell.

Just take a walk down lonely street

to Heartbreak Hotel.

That song expressed my mood quite accurately. The lonely one in me loved knowing that if I took a walk down lonely street I’d find company at the Heartbreak Hotel. The poet in me loved the deep feeling, the images and word play. However I lived in a cultured family in which Elvis was seen as the lowest of low culture. Taboo. If I wanted access to the power of music to express suffering, why not listen to Bach’s Saint Matthew’s Passion or the Mozart Requiem? I liked Bach and Mozart just fine, but they weren’t sexy, they didn’t dance and grind their hips while they sang about their loneliness. It would be many years before I felt the inner freedom to appreciate Elvis, and follow his lineage back to the Blues where I found so much to love—so much beauty, wisdom and humor in the expression of terrible suffering. Here are some of the lyrics to Howlin Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightnin’” with it’s intense poetic imagery and sound, evoking lost radiance and abandonment.

“Smokestack Lightnin’”

Ah oh, smokestack lightnin'

Shinin' just like gold Why don't ya hear

me cryin'?

me cryin'?

A whoo hoo, whoo hoo, whoo

Whoa oh tell me, baby

What's the matter with you?

Why don't ya hear me cryin'?

Whoo hoo, whoo hoo, whooo

Whoa oh tell me, baby

Where did ya, stay last night?

A-why don't ya hear me cryin'?

Whoo hoo, whoo hoo, whooo

Whoa oh, stop your train

Let her go for a ride

Why don't ya hear me cryin'?

Whoo hoo, whoo hoo, whooo

With Rock and Roll and the Blues we have moved from abandonment by God to abandonment by a lover. The “whoo hoo” of Howlin’ Wolf’s cry, is the whistle of the train pulling out of the station, is the wisdom that as we suffer life moves on and we never know where we’ll find ourselves next.

Sea Glass

Suffering has been a major Muse for my dear friend Gilda Frantz, who, in her late 80s, has just published her first book: Sea Glass: A Jungian Analyst’s Exploration of Suffering and Individuation.

Why “Sea Glass?” Frantz writes:

Gilda is direct, wise, beautiful and very funny. She has been writing all her life, but has never taken her writing seriously enough to gather it into a book. Luckily, she listened to an inner voice who led her to give us Sea Glass—a collection of her essays, talks and interviews, a treasure trove of gems from her long, rich and difficult life. It has been Gilda’s fate to witness the sudden death of several beloved family members. One of them was her husband, Kieffer Frantz, who was a Jungian analyst and much-respected member of the Los Angeles Jung Institute. She writes:

Suffering has been a major Muse for my dear friend Gilda Frantz, who, in her late 80s, has just published her first book: Sea Glass: A Jungian Analyst’s Exploration of Suffering and Individuation.

Why “Sea Glass?” Frantz writes:

As a child I had no way of knowing that these gem-like stones were originally broken shards of bottle glass that somehow wound up in the ocean…Were they wine bottles tossed over the side of an ocean liner plowing the wine–dark sea? Were they once carriers with a message a lonely person wrote on a desolate island in the middle of nowhere?… Once the glass was a vessel and now it is only a piece of what it once was…

When I was casting about for a title for my book, the image of a piece of sea glass came to me. It dawned on me that the process the glass endures in the ocean is not dissimilar to what happens psychologically when a person is wounded, broken, and goes through life’s capricious twists and turns. We either drown in the sea, or if we can get a foothold possibly our fate changes and we can begin to grow consciously…

Gilda is direct, wise, beautiful and very funny. She has been writing all her life, but has never taken her writing seriously enough to gather it into a book. Luckily, she listened to an inner voice who led her to give us Sea Glass—a collection of her essays, talks and interviews, a treasure trove of gems from her long, rich and difficult life. It has been Gilda’s fate to witness the sudden death of several beloved family members. One of them was her husband, Kieffer Frantz, who was a Jungian analyst and much-respected member of the Los Angeles Jung Institute. She writes:

Gilda, who, had been abandoned by her father as a child, found a relationship to the archetype of the “good father” in her marriage. Now, she was abandoned once again. Gilda has a mythopoetic sensibility and often uses etymological research to deepen the meaning of words. I learned something vital from her comments about the word abandonment:After my husband’s totally unexpected death when I was only in my late forties, I was eaten up by loneliness. For months I felt as though the house had a zipper that shut me out of life, and kept life out of my house I lived in the realm of the dead.

Abandonment is a fateful experience in which we feel we have no choice. We feel alone, as if the gods are not present… The word abandonment means literally “not to be called.” It is etymologically connected with the world fate, which means “the divine word.”Sea Glass is full of such luminous moments, bringing meaning to painful experience. It is also full of humor. When Patricia Damery and I began gathering essays for our book Marked by Fire: Stories of the Jungian Way, I knew I wanted to ask Gilda for a piece, because she writes so directly out of her lived experience. We were delighted with “The Greyhound Path to Individuation,” in which she tells the tumultuous story of her difficult childhood with charm and wit. I was pleased to revisit it as the opening chapter of Sea Glass. Here’s an excerpt:

In the summer of 1938, I was 11 years old and being tossed back and forth, like a potato latke, between my mother in California and my father on the East Coast…I was beginning to do what my mother called “develop.” My “developing” worried my mother so much that even though we loved one another, she was tossing me back to my father. One morning she told me, “You are going to live with your father, the rat; I can’t take care of you anymore.”Gilda is an inspiration to me and to many others in our community. She has learned from her suffering, learned that to “be alone and not lonely…is the treasure hard to attain and the pearl of great value.” It is, she writes “to be in contact with the inner divine; that inner light in which there is no darkness and no fear.” Reflecting on Elvis and Howlin’ Wolf’s songs in the light of her wisdom, deepens my understanding of the power of their work. Recently I had to go through a difficult experience. I found myself clutching Sea Glass almost as a transitional object. Reading Gilda’s voice was a comfort and a blessing.

Suffering has always been a major Muse for me. If I can write about it, I have found, I can suffer it and glean meaning from it. I believe I am in good company here, with the Psalmist, Elvis and Howling Wolf and Gilda. And so I close with a poem about suffering, from The Faust Woman Poems.

Because of What Aches

Because your knee, like the knee of your father before you

prophesies rain

Because you’re as weather beaten as the willow

which creaks in the night

Because your hips are as surly

as a girl at fourteen—fire tamped down and smoking—

Because your knuckles are cranky, remembering

your grandmother fumbling with buttons, with jar lids

Because words have failed with your brother

don’t do much good with your son

prophesies rain

Because you’re as weather beaten as the willow

which creaks in the night

Because your hips are as surly

as a girl at fourteen—fire tamped down and smoking—

Because your knuckles are cranky, remembering

your grandmother fumbling with buttons, with jar lids

Because words have failed with your brother

don’t do much good with your son

Because your neck tries to rise above

an aging tangle of knots

Because you’ve given yourself to the wild ride—chased after toddlers

broken commandments, had words with the owl on the roof—

Because your eyes long for the mountain

Because the old rose still blooms

You’re not ready for ash, or thin air

Submit to the fire your early drafts

your sagas of shame, your lost directions

The truth is—you’re still tied to this ferment—

because of what aches

because of what aches