so I could talk to you about the light… and you

could tell me again how the light of late

afternoon is so different from the light

of morning

from “Oma”

Naomi Ruth Lowinsky

|

| Ancient Ways -by Diana Bryer |

To be blessed by an elder, especially an admired one, one whose wisdom and accomplishment one wants to emulate, is a gift. My Oma, a painter, gave me the gift of her blessing, opening me to my own creative path when I was a girl. Her spirit has illuminated the long spiral path of becoming myself—what Jungians call individuation—often a lonely business.

On the way to being an elder myself, hopefully a giver of blessings, I am amused to notice that receiving the blessing of elders continues to matter—a lot. I find myself musing about my Jungian tribe and the elders who have illuminated my way. The Jungian way follows the archetype of initiation, in which elders bring the young into the tribe in many ways: analysis, consultation, the reviewing and certifying committees of the Institute. I was lucky in my mentors on the way to becoming a Jungian analyst— I felt understood, supported and appreciated.

But I’ve been musing about the unofficial forms of initiation, which by their unplanned and spontaneous nature may have more to do with the peculiarities of one’s path. Though my memory is nothing to brag about these days, I have a stepping stone path of memories of elders who have blessed me.

The story I want to tell is about Elizabeth Osterman, she of the intense and piercing eyes, the fierce no nonsense way of leaping from unconscious to conscious and back. I had no official relationship with her, but she was a powerful presence for me. Osterman happens to be my Oma’s maiden name, so I considered Elizabeth a grandmother, though I never told her this.

I also never told her that she had changed my life, years before I knew her, years before I thought of becoming an analyst. I was lost in my life. A friend invited me to a conference called The Forgotten Feminine. I had no idea what that meant but it tugged at me. Elizabeth Osterman was one of the wise older women who spoke at the conference about women’s psychological development, about the importance of supporting a woman’s creativity. She made a deep imprint on my soul, gave me an image of what a Jungian analysis could do. I found myself an analyst.

Fifteen years later, when I was a new candidate at the San Francisco Institute, Elizabeth placed herself at the bottom of the steps as I descended, glared at me and said in a voice of great authority: “You are a poet. You must honor that path.” I’m not sure where she got her certainty. Perhaps she had seen some of my writing. But her voice rang loudly in my head for years during which I ignored the call of my Muse. I remember feeling much more guilty toward Elizabeth than I did toward my Muse.

Fifteen years later, when I was a new candidate at the San Francisco Institute, Elizabeth placed herself at the bottom of the steps as I descended, glared at me and said in a voice of great authority: “You are a poet. You must honor that path.” I’m not sure where she got her certainty. Perhaps she had seen some of my writing. But her voice rang loudly in my head for years during which I ignored the call of my Muse. I remember feeling much more guilty toward Elizabeth than I did toward my Muse.

Fifteen years later, when I was a new candidate at the San Francisco Institute, Elizabeth placed herself at the bottom of the steps as I descended, glared at me and said in a voice of great authority: “You are a poet. You must honor that path.” I’m not sure where she got her certainty. Perhaps she had seen some of my writing. But her voice rang loudly in my head for years during which I ignored the call of my Muse. I remember feeling much more guilty toward Elizabeth than I did toward my Muse.

Fifteen years later, when I was a new candidate at the San Francisco Institute, Elizabeth placed herself at the bottom of the steps as I descended, glared at me and said in a voice of great authority: “You are a poet. You must honor that path.” I’m not sure where she got her certainty. Perhaps she had seen some of my writing. But her voice rang loudly in my head for years during which I ignored the call of my Muse. I remember feeling much more guilty toward Elizabeth than I did toward my Muse.

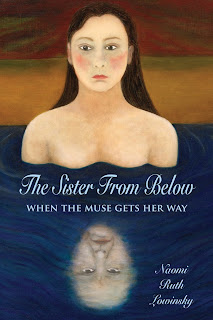

When I gave the paper that became the beginning of The Sister from Below: When the Muse Gets Her Way, in which the Muse asserts herself in me, a paper that included my poetry, Elizabeth sat herself down in the front row, her cane erect between her feet, her short white hair bristling. When I was done she rose, gave me that intense glare, and said: “Now you’re doing it. It’s about time!”

That was many years ago. Elizabeth is long gone. But her blessing feels vibrant and alive in my soul. Here is part of a Dirge I wrote at the time, some fifteen years ago, when many beloved Jungian elders of our Jungian tribe died, including Elizabeth:

There are those whose words

change the course of the river

before we ever meet

their eyes

On the day you died

Elizabeth

I was writing a poem

about the great green frog

that jumped into my reverie—

the frog that wonders in

and out of women’s wombs

tells the story

of the old she god

you were the first

to bring me news of—

You stood

on a university platform

in Wheeler Auditorium

where I had heard

many famous professors

but no one had ever told me—

that a woman

writing down her dreams

can spiral inward

to her dark center

and come back out

with flaming colors

and her own wild tongue!

(published in red clay is talking p. 97-8)

|

| Marked by Fire |

When Patricia Damery and I began working on our collection Marked by Fire: Stories of the Jungian Way, we knew we were working in the tradition of a lineage of elders. We dedicated our book to the late Don Sandner, who had been a significant elder for both Patricia and me. But when Suzanne and George Wagner agreed to review the book, neither one of us was prepared for how much their response would mean to us.

|

| Matter of the Heart, a film created by Suzanne and George Wagner |

Suzanne and George are our forebears in the endeavor to give voice to the Jungian worldview. They brought the inner life as we Jungians understand it into films such as Matter of Heart —a portrait of Jung, The World Within, which provided glimpses into Jung’s Red Book decades before it was published and the Remembering Jung Series in which the Wagners were blessed by elders who shared memories of their experiences with Jung.

Patricia and I had been moved and delighted to find colleagues who could express their experience of living in relationship to their own inner lives—dreams, synchronicities, active imagination. I was moved and delighted all over again to read George and Suzanne’s words in their two separate reviews just published in The Jung Journal (Spring 2013 Vol. 7, #2).

George wrote:

Readers will be moved, saddened, and challenged by the notion that to strive for individuation is truly difficult, heavy, hard work. But it appears to be worth it—not only for yourself, your colleague, and your family, but also for the planet….

In these true-life adventures in the search for soul, these “lucky 13” individuals provide living examples to assist us in conquering our own fears. The fire that ignites in the soul can be formidable. These stories give us courage and guidance….

Thank you, George. Gathering stories that would support others in their search for soul was exactly what we hoped to achieve. Suzanne wrote:

Reading such rich, self-disclosing material…we are left with no doubt that a truly transformative power that is both dangerous and beneficial resides in the unconscious psyche….

Clearly the path of individuation is a demanding adventure that involves suffering.…Jung often appears to these writers in dreams and active imagination as a guide who both challenges and supports the process. It seems he has become an active ancestral presence in the soul of the next generations!Thank you Suzanne. It is hard to express how moved and delighted I am by your words: It seems [Jung] has become an active ancestral presence in the soul of the next generations! You and George have worked hard to make Jung’s ancestral presence and influence available to future generations through film. I am so grateful to you for that. I don’t think I got it until I read your words— Patricia and I, in our way, have been carrying on your work. We have gathered a tribal record of Jung as ancestor. To have you recognize that is a profound blessing.